The only true wisdom is in knowing you know nothing

– Socrates

On the fiftieth anniversary of the 1929 market crash, investment manager Robert Kirby published an essay describing how each generation fails to learn the lessons of the past.[1] Comparing the late 1920s with the institutionally dominated investment markets of his day in 1979, Kirby discovered that there were more similarities than differences between the two periods. He noted that the 1920’s was characterized primarily by reckless speculation, and fifty years later, Kirby argued that institutions merely appeared to be “investing” through their extensive use of expensive research and computers. In the late 1920s, most investment managers would have openly laughed if someone suggested they visit with company management before buying or selling its stock. Kirby claimed the candid response would have been, “What does the company have to do with whether or not the stock is going up?”

Kirby observed that most 1979 investment institutions possessed impressive features, including an extensive staff of analysts backed by economists, demographers, and other specialists. This was typically a sham, as although these institutions had the horsepower and expertise needed to function as true “investors,” their behavior resembled the manic trader who shunned fundamental research. Kirby believed that many of the day’s decisions were based more on a technician’s secret interpretation of a price chart than on a careful evaluation of a company’s future operating performance.

Financial markets are not immune to fads and trends. The stock market of the early 1970s was no exception, despite the danger signs visible to any prudent investor. In November 1967, Warren Buffett began to temper the expectations of his investment partners in the Buffett Partnership Ltd. He highlighted that the partnership of $20 million invested in “controlled companies” (i.e., unlisted subsidiaries) and $16 million in short-term government debt would not benefit from any potential stock market rally. This decision was primarily a reflection of Buffett’s inability to “find any obviously profitable and safe places to put the money.” By May 1969, Buffett called it quits and wrote to advise his partners that he was closing the partnership: “I just don’t see anything available that gives any reasonable hope of delivering a good year, and I have no desire to grope around, hoping to “get lucky” with other people’s money. I am not attuned to this market environment, and I don’t want to spoil a decent record by trying to play a game I don’t understand so I can go out a hero.”

While Warren Buffett was in the process of exiting the stock market, other market participants pursued a group of stocks that would later be known as the ‘Nifty Fifty’. These glamour stocks included IBM, Gillette, Coca-Cola (KO), and Xerox (XRX). This subset of stocks promised stability; none of these companies had cut their dividends since World War II. Coupled with their exceptional growth prospects, including international expansion, investors justified paying any valuation multiple for these stocks. The ‘Nifty Fifty’ gained a reputation as ‘one decision’ stocks: the only decision revolved around how much to buy, confident that these stocks would defy any weakness in the global economy. By 1972, the S&P 500 index (SP500) was trading at a rich multiple of nineteen times annual earnings. In contrast, the ‘Nifty Fifty’ traded at an average multiple of forty-two times annual earnings. Several companies with the ‘Nifty Fifty’ reached absurdly optimistic levels. Avon Products traded at sixty-five times earnings, Walt Disney (DIS) at eighty-two times earnings, McDonald’s (MCD) reached a multiple of eighty-six times earnings, while Polaroid eventually achieved a price-earnings multiple of ninety-one.

The music abruptly stopped on January 11, 1973. In the words of a Forbes columnist, companies within the Nifty Fifty “were taken out and shot, one by one.” Following their respective stock price peaks, Xerox stock fell by 71%, Avon Products fell by 86%, and Polaroid’s price collapsed by 91%. A post-mortem analysis by Forbes summarized the devastation: “What held the Nifty Fifty up? The same thing that held up tulip-bulb prices in long-ago Holland – popular delusions and the madness of crowds. The delusion was that these companies were so good it didn’t matter what you paid for them; their inexorable growth would bail you out. Obviously, the problem was not with the companies but with the temporary insanity of institutional money managers – proving again that stupidity well-packaged can sound like wisdom. It was so easy to forget that no sizable company could possibly be worth over fifty times normal earnings.”

If one participates long enough in the investment markets, they realize human nature never changes. Similar to the ‘Nifty Fifty,’ a few immensely popular global technology mega-cap stocks have captivated the attention of today’s market participants. Last decade’s financial repression drove interest rates to zero, effectively destroying the appeal of cash and bonds as relevant asset classes for many investors. In their search for positive real returns, investors have been enticed by the allure of the equity markets. Both institutions and individual investors view this limited group of large technology stocks as the safest, most dominant, and rational choice to own in today’s uncertain environment. While these businesses may prove enduring, the safety of an investment is ultimately a function of price and value. A stock represents a claim to a future cash flow that an investor expects to receive. The long-term returns an investor expects from those cash flows are inseparable from the price paid.

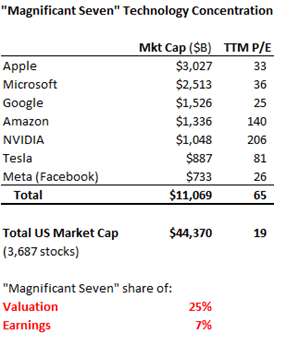

Last year’s mild stock market pullback reversed in October, as market participants such as retail investors, exchange-traded funds, institutions, and hedge funds piled back into the shares of Apple (AAPL), Microsoft (MSFT), Google (GOOG,GOOGL) , Amazon (AMZN), Nvidia (NVDA), [[Meta]], and Tesla (TSLA). These stocks were deemed the most liquid and considered “cheap” enough to own in size. This year, Artificial Intelligence (AI) is the new pixie dust, further enticing participants deeper into market darlings. Presently, every Wall Street analyst makes the case that these technology giants will disproportionately benefit from the AI boom. The excessive hype surrounding AI to justify forward earnings estimates and current valuations may seem absurd but is not unexpected—it follows the same pattern every cycle. Or, as Kurt Vonnegut once wrote, “History is merely a list of surprises. It can only prepare us to be surprised yet again.”

Bloomberg Data; July 3, 2023

Apple and Microsoft together possess a market value exceeding $5.5 trillion. If one includes Nvidia, with a market value of just over $1 trillion, the cumulative worth of these three companies nearly matches the entire economies of France ($2.8 trillion) and Germany ($4.1 trillion). This comparison highlights the extraordinary valuation, rivaling two of the world’s largest industrial economies. Further, this sum ignores Google ($1.5 trillion) and Amazon ($1.3 trillion). Apple, Amazon, Microsoft, Google, and Nvidia have largely driven the percentage gains in the US stock market this year. In fact, Apple and Microsoft now account for almost 15% of the market capitalization of the S&P 500 index, the largest percentage total for any two companies since 1980 (IBM and AT&T).

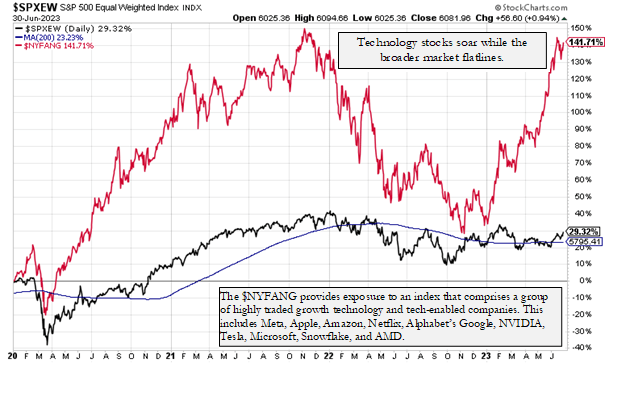

If the S&P 500 was weighted equally, rather than by market capitalization, its performance over the last three years looks anemic. The equal weight index provides a better understanding of the breadth of the market and the economy. Of course, not all stocks are equal, as some hold greater significance than others. Some businesses are poised to benefit and grow more due to the ongoing AI revolution. One could argue that the aforementioned five companies provide substantial exposure to AI, potentially unleashing a wave of creative destruction. However, caution is warranted when 25% of the entire U.S. stock market capitalization is concentrated in just seven technology companies, trading at materially different earnings multiple of the remaining 3,687 businesses

The AI ‘bell cow’ leading the new investment narrative is Nvidia, currently priced at a level where its free cash flow yields only 0.45% for its shareowners; by comparison, riskless U.S. Treasury Bills now yield 5.3%. Unfortunately, 70% of Nvidia’s meager cash yield of 0.45% is further eroded by stock-based compensation (SBC) for its employees and management. The company’s stock compensation plan consumes $2.8 billion of the company’s $28 billion annual revenue but shares outstanding have not decreased. Nvidia’s market capitalization is 37% greater than Berkshire Hathaway (BRK.A, BRK.B). However, when comparing fundamentals, Berkshire Hathaway generated $23 billion in free cash flow over the past four quarters while Nvidia generated only $2.6 billion (SBC adjusted). Furthermore, Berkshire Hathaway does not dilute shareholders with stock-based compensation. Despite a wide array of available investment options, market participants have overwhelmingly favored a select few dominant technology companies.

At its current price of $423, Nvidia is valued at forty times its annual revenue. If one heroically assumes that the company manages to compound revenue by 50% per year for three years, it will “only” trade at a multiple of twelve times hypothetical sales in 2026…hardly a screaming bargain. Of course, market history has an interesting way of repeating itself. The most exaggerated technology bubble occurred in 1928-29 when the Radio Corporation of America (RCA) captured the imagination of every speculator on Wall Street. RCA’s trading volume sometimes accounted for 20% of the total volume on the New York Stock Exchange. At the stock price peak in September 1929, the company was “valued” at $665 million. Sales increased from $65 million in 1927 to $102 million in 1928 to $182 million in 1929. Therefore, at the peak of the RCA stock buying frenzy, the company was “valued” at a multiple of “only” 3.6 revenue. Forty-five years later, in 1974, RCA’s annual sales were $4.6 billion, yet the stock price bottomed that year at $38, about one-third of its 1929 stock price high.[2]

While most rational investors consider Nvidia ‘slightly’ overvalued, market momentum could push fantasy valuations higher. Comparing the 1929 period of RCA and the current situation with Nvidia in 2023, one observes a similar pattern where most stocks experience decline while a handful of large companies powered the major indices higher. In both instances, unsuspecting investors maintained the illusion that the “market” was healthy.

In 1929, the financial press reported that the “big trusts” were primarily buying “blue chips,” liquid and “safe” components of the Dow Jones Industrial Average. These institutional trusts understood that the economy stood on shaky ground, but the music played, and they had no choice but to continue dancing. A similar phenomenon is occurring today, with institutions concentrating on a select group of technology companies that offer both liquidity and size suitable to accommodate their trading strategies. As a result, the stock market indices push higher while the broader market stagnates. Notably, during both periods, the U.S. Federal Reserve Bank was raising interest rates as the economy slid into some form of contraction. The only thing more painful than learning from experience is failing to learn from experience.

Many investors hold the belief that last year’s market experience was a “worst-case scenario”. However, it is possible that 2022 is merely the beginning of a much larger process aimed at addressing the most significant bubble in history. The personality of the stock market in recent years has been characterized by a speculative fervor as extreme as previous asset bubbles. Such a manic stock market environment, which gave birth to meme stocks and over 23,000 different cryptocurrencies, does not fade away without leaving echoes. As bubbles deflate, one can expect the resurgence of speculative behavior.

In the second quarter, the rekindling of animal spirits among active traders draws in a multitude of passive investors. This includes individuals regularly purchasing index funds for their retirement accounts, which further channels more funds to the most overvalued stocks driven by speculative activities. Additionally, volatility-targeting funds like risk parity strategies are compelled to put massive amounts of money to work in the stock market due to the success of participants in pushing prices higher. By employing extreme leverage through short-dated options, systematic fund flows create powerful forms of market misdirection that have nothing to do with company fundamentals.

From a value investor’s perspective, the misbehavior of the stock market may simply be that markets have behaved irrationally for so long, with the full endorsement of U.S. Federal Reserve policy, that most are reluctant to accept rational expectations. As concerning as that may be, one can take some comfort in Warren Buffett’s assertation that one should never bet against America. The United States remains the world’s richest, most productive, and most innovative economy. America enjoys several benefits over other major economies: prominent levels of education, better demographics, the rule of law, a more flexible economic system than Europe, and a healthier and fairer economic and political system than China. If one invested $100 in the S&P 500 in 1990, it would be worth $2,000 today, four times what would have been earned elsewhere in the developed world.

However, this statistic fails to account for the enormous growth of debt and the steady fall in the dollar value, in which the S&P 500 is denominated, over the past three decades. These factors have greatly inflated valuations, raising doubts about the likelihood of similar future gains. If the S&P 500 were to repeat this performance, it would trade at 80,000 in 2052. Achieving such a milestone would necessitate further significant inflation and currency debasement. Over the last three decades, America’s growth came not from superior economic management or policy but from an explosion of public and private sector debt and government spending. This is not success, but rather an illusion of prosperity enjoyed by a shrinking percentage of the American population.

The last century has been kind to America, and perhaps the next hundred years will follow suit. However, present-day America now confronts the challenge of inflation. To generate inflation-adjusted real rates of return, interest rates must move higher. Financially, it is nearly impossible due to excessive amounts of debt in our country’s economy, making it difficult to refinance at higher interest rates. Economically, too many companies depend on low-interest rates to support their current business model. Additionally, the U.S. government’s interest expense is now $929 billion annually, soon to exceed one trillion dollars or equivalent to the country’s entire defense budget. Over the past decade, U.S. government debt grew from $15 trillion to $32.4 trillion, a level only comparable to that after WWII.[3]

Against this incongruous backdrop it’s remarkable to consider the year-to-date performances of some of the magnificent seven technology stocks: Apple is up 50%, Amazon is up 55%, Facebook is up 138%, and Nvidia is up 190%. One cannot help but sense the distant echoes of March 2000, when the Nasdaq Composite peaked at over 5,000. After plunging by 80% over the next two years, the Nasdaq Composite took fifteen years to regain that 5,000 level. This is a typical market pattern when one grossly overpays for an asset, even a high-quality company like Apple—overpaying today pulls forward future investment returns. The net result is that first, one loses money, and then one loses time.

When Warren Buffett wrote to partners of the Buffett Partnership in 1967, he warned “The market environment has changed progressively, resulting in a sharp diminution in the number of obvious quantitatively based investment bargains available. We will not follow the frequently prevalent approach of investing in securities where an attempt to anticipate market action overrides business valuations. Such so-called ‘fashion’ investing has frequently produced substantial and quick profits in recent years. It does not completely satisfy my intellect and most definitely does not fit my temperament. I will not invest my own money based upon such an approach – hence, I will most certainly not do so with your money.” Fifty-five years later, one wonders how this message might be received today.

Investor and historian Jeremy Grantham noted that the central truth of the investment business is behavior is driven by career risk.[4] Grantham cited English economist John Maynard Keynes, who emphasized the prime directive is first and last to keep your job. Keynes explained that one must never, ever be wrong on their own. To prevent this calamity, professional investors pay ruthless attention to what other investors are doing and “go with the flow.” The result is herding, or momentum, which drives prices far above or far below fair value. Price momentum explains the discrepancy between a remarkably volatile stock market and relative stable economic growth. Missing a large move in the stock market, however unjustified it may be by fundamentals, is to take an enormous career risk. Professional herding will always dominate investing, and short-term price movements will always be exaggerated.

Although a corporation’s future value stretches decades, or as GMO’s Ben Inker has written, two-thirds of all corporate value lies beyond twenty years; markets often focus solely on the next four quarters. Keynes wrote in General Theory that the investor will be perceived as “eccentric, unconventional and rash in the eyes of average opinion … and if in the short run, he is unsuccessful, which is very likely, he will not receive much mercy.” Value-oriented firms that have the responsibility of investing their clients’ long-term savings through fundamental analysis can relate to Keynes’ remarks. Preserving investment capital from external factors such as inflation and taxation is already a challenging task, and it becomes more complex if recklessness and career risk is involved in the investment selection process. When entrusted with the capital of others, it is vital not to engage in an environment where actions are driven by expectations rather than by what is truly right.

Today, the best explanation for the surge in market prices is the widespread belief among investors that the U.S. Federal Reserve will begin lowering interest rates later this year. Whether this belief holds true or not is not important. What matters is the market firmly believes and has consequently acted, herding into the assets perceived as the most responsive to lower interest rates. While market participants are entitled to their opinions, anyone believing the overall market is reasonably valued and will provide attractive risk-adjusted returns over the long term must disregard a plethora of sobering facts. Based on any historically reliable valuation metric, the S&P 500 index is more expensive than any level in history before October 2020, including 1929 and 2000. Higher interest rates will eventually weigh on stocks by suppressing economic activity and subsequently pressuring company profits. The current technology-led rally can only mask an underlying economic weakness for a limited period.

Returning to Robert Kirby’s perspective in 1979, he expressed a belief that a portfolio of marketable securities should be managed like a real estate portfolio. The typical real estate commitment is made in anticipation of projected cash flows versus expenses; the investor develops an estimated future internal rate of return based on the property’s predicted net cash flows. To meet an anticipated investment return, the investor does not have to assume that he can sell the property at a higher price to someone else later; rather he or she adopts the mindset of a private owner of assets. Kirby advocated that a portfolio of common stocks should be constructed, and their future returns measured, by the same set of criteria. In times of apparent prosperity, it’s crucial to examine and scrutinize the underlying reasons to ascertain whether current prosperity is genuine or merely an illusion. Kirby’s advice provides a valuable guide in the current investment landscape saturated with the illusion of prosperity.

With kind regards,

St. James Investment Company

Footnotes[1] Robert Kirby, “Lessons Learned and Never Learned,” The Journal of Portfolio Management, June 1979, 52-55. [2] Fleckenstein Capital, May 31, 2022, www.fleckensteincapital.com. [3] U.S. National Debt Clock : Real Time [4] Jeremy Grantham, “My Sister’s Pension Assets and Agency Problems,” GMO Quarterly Letter, April 2012. © 2023 St. James Investment Company |

Original Post

Editor’s Note: The summary bullets for this article were chosen by Seeking Alpha editors.

Read the full article here