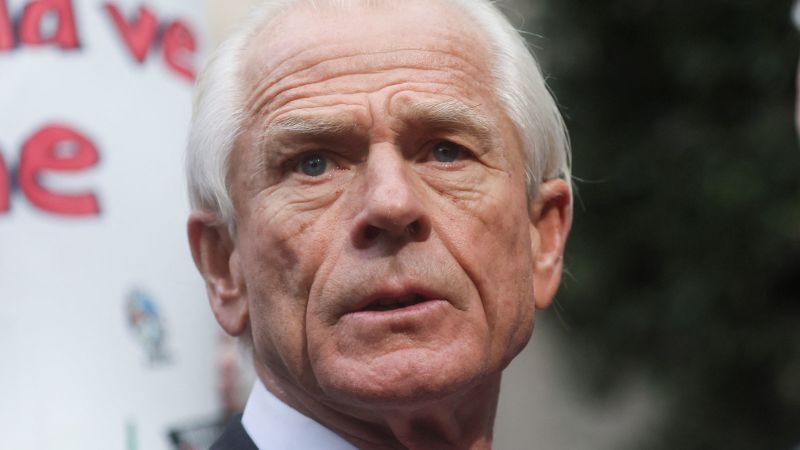

The swift conviction of Donald Trump’s former trade adviser Peter Navarro for contempt of Congress sent two warnings to the multiple co-defendants in the ex-president’s approaching criminal trials.

The first is that nobody, not even former White House big shots claiming to be empowered by presidential authority, is above the law.

The second is that loyalty to Trump can be hazardous and often gets those who show it cross-wise with the law.

Navarro was convicted on Thursday for not complying with a subpoena from the House select committee that investigated the January 6, 2021, attack on the US Capitol. That panel doesn’t even exist anymore – it was ended by the Republican House majority that took over this year – but the verdict reinforced the principle that citizens cannot ignore congressional investigations. The symbolism of the jury’s decision will reverberate far beyond this trial, which will be remembered not for Navarro’s claims it represented a seminal constitutional battle, but for what the judge described as the “pretty weak sauce” of aspects of his defense.

It showed how the rule-breaking defiance that powers Trump’s political operation often runs into a brick wall when it comes up against the courts, where bluster and false narratives have to submit to cold hard facts.

This tradition was established in Trump’s presidency when far-reaching moves on issues like immigration were blocked by judges. It was cemented when Trump’s claims of fraud in multiple states after the 2020 election created powerful political momentum among his supporters but were abruptly thrown out of courts because they lacked standing or merit. While the Navarro case is fairly basic compared to Trump’s four criminal probes, it is a cautionary tale that poorly crafted defenses can quickly crumble in court where the standards of evidence, rather than propaganda and political dark arts, prevail.

Still, Trump and his acolytes may take away something different from this warning. Navarro, for example, who is is unrepentant and a true Trump believer, pledged to appeal based on executive privilege issues. He called Trump a “rock” after his trial, predicting that the former president, who’s the front-runner for the GOP nomination, will retake the White House in 2024. His enduring allegiance to his former boss, despite the legal jeopardy that loyalty has found him in, underscores how some in Trump’s orbit are operating with difference incentives in mind. Casting their trials as principled political stands might be useful, for example, to prove their faith in the ex-president (and continue receiving help with legal bills) or to boost their own profiles in the conservative media world.

“I love President Trump. He’s been very supportive of me,” said Navarro, who may be eying a return to the White House – and a possible pardon – if the ex-president wins back the presidency next year. Another of Trump’s boosters and one-time political guru, Steve Bannon, was once pardoned by Trump. And now he is portraying his own conviction for contempt of Congress, for which a four-month jail sentence is on hold pending appeal, as an example of political persecution.

The verdict came down as many of Trump’s co-defendants in his forthcoming trials in Washington, DC, and Georgia over election subversion and in Florida related to his mishandling of classified documents confront the harrowing consequences of being a criminal defendant. That includes legal bills and, like Navarro, the eventual possibility of a spell in prison.

This could be a complicating factor for Trump, especially in Georgia, where Fulton County District Attorney Fani Willis has constructed a vast racketeering case involving 19 accused. Such a strategy is often used in organized crime cases where lower-ranking defendants are peeled off by prosecutors to give testimony against the alleged leaders of a conspiracy. Few of the potential witnesses in the Willis case, which alleges a sprawling scheme to steal the 2020 election, are rich celebrities or highly paid lawyers, and the temptation to turn on Trump to save themselves could be rising.

One Trump employee caught up in the Florida classified documents case seems to have already evaluated their options. Mar-a-Lago IT worker Yuscil Taveras has struck a cooperation agreement with the special counsel’s office, Taveras’ former defense attorney said in a court filing this week. Tavares had been threatened with prosecution and will now escape such a fate after agreeing to testify.

Legal analysts said Taveras’ deal was a breakthrough for special counsel Jack Smith. And CNN previously reported that his testimony before a grand jury in July was the source of new allegations against Trump and two co-defendants, including over alleged efforts to delete incriminating security footage at the club.

“I think it’s big news, the fact that the defendants are starting to flip on one another,” former federal prosecutor Karen Friedman Agnifilo said on “CNN News Central” on Wednesday. “I think it’s going to be a big deal that you’ve got an insider who’s going to now be able to testify about the efforts not only to possess these classified documents, but to evade law enforcement … he’s going to be able to talk about the cover up,” Agnifilo, a CNN legal analyst, said. Trump and the two co-defendants in the case, longtime valet Walt Nauta and Mar-a-Lago property manager Carlos de Oliveira, have pleaded not guilty.

How people get seduced into Trump’s orbit … and legal woes

One key political figure who was seduced by Trump world was Mark Meadows, a former North Carolina congressman who took a job as White House chief of staff and walked into a legal quagmire. Meadows is waiting to hear whether he’ll succeed in his bid to have his trial in the Georgia election subversion case moved to federal court, where he hopes to have it dismissed. Meadows essentially argued in a hearing this week that he was simply doing his job when he was setting up meetings and calls on which the then-president tried to overthrow the election in Georgia and other states. Meadows, like every other defendant, is innocent until proven guilty. But arguing that he was performing the duties of a government official stops being a viable defense when activity allegedly crosses a criminal threshold.

Trump doesn’t seem to be taking any chances that another of his close associates, former New York Mayor Rudolph Giuliani, is forced by a mountain of legal bills to seek his own deal with prosecutors. While Trump has pushed back on the idea that he should pay his former attorney’s legal bills himself, some sources told CNN, he hosted on Thursday the first of what is expected to be two fundraisers he will sponsor for Giuliani at $100,000-a-plate at his golf club in Bedminster, New Jersey.

Giuliani – a co-defendant in the Georgia case where he faces 13 counts, who also lost a defamation lawsuit from two Georgia election workers – hopes to make a dent in millions of dollars in legal bills, a source familiar with the matter told CNN. Giuliani had visited Mar-a-Lago in recent months to make a desperate appeal to the ex-president for help paying his legal fees, CNN’s Kaitlan Collins and Paula Reid reported last month.

The cases of Giuliani and Meadows highlight the way that people with high profiles and public reputations walked willingly into Trump’s inner circle – perhaps drawn by the chance to be close to power or the ex-president’s glaring spotlight – and ended up in the clutches of the legal system.

Bannon and Navarro are far from the only members to find out that it’s best to enter Trump’s inner circle with a lawyer close at hand.

Another key lieutenant, Allen Weisselberg, was sentenced to five months in jail after testifying as a witness against the Trump Organization over a decade-long fraud scheme. Another former Trump functionary, lawyer Michael Cohen, went to jail for tax fraud, lying to Congress and campaign violations for helping to pay off two women who claimed they had affairs with Trump. The ex-president denied the claims.

And hundreds of Trump supporters who believed they were acting on the former president’s wishes have been convicted for their role in the mob attack on Congress on January 6, 2021, while Biden’s victory was being certified inside the Capitol. Just this week, several key members of the far-right Proud Boys group were sentenced to jail terms of more than a decade for their role in the attack.

It’s not as if all of these Trump followers and associates were not warned. Way back in his presidential term, Trump’s former 2016 campaign chairman Paul Manafort went to prison after admitting to money laundering, tax fraud and to illegal foreign lobbying after catching special counsel Robert Mueller’s eye in the Russia probe. And Trump’s first national security adviser Michael Flynn pleaded guilty to lying to the FBI about conversations with Russia’s ambassador to Washington. Trump pardoned both men, which again, could be offering a reason for this year’s accused to remain in Trump’s good graces should he return to the White House. (A CNN poll released Thursday found no clear leader in a hypothetical matchup between Biden and Trump.)

Up until now, Trump associates often paid a heavy price for falling afoul of the law while their leader escaped. But with Trump facing 91 charges across four criminal trials, accountability could look different this time.

Read the full article here