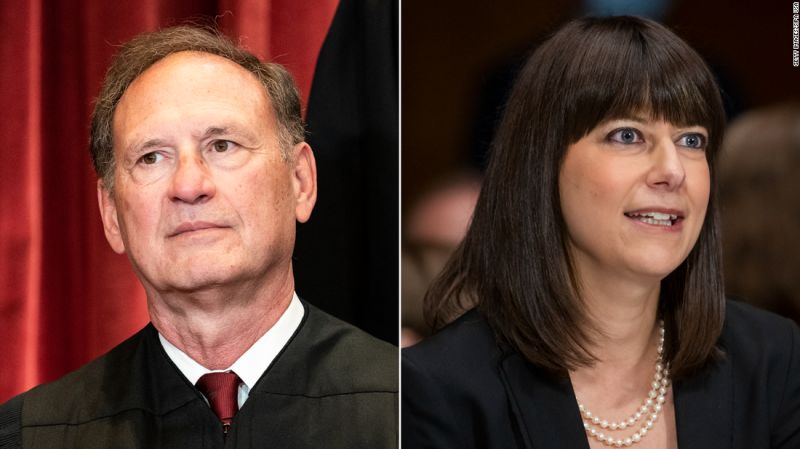

Justice Samuel Alito is the tip of the spear for conservatives challenging the Biden administration during oral arguments at the Supreme Court.

He’s a fierce questioner, ready to trap advocates in their arguments. And he becomes demonstrably riled when he fails to get the answer he wants. He shakes his head and rolls his eyes.

Solicitor General Elizabeth Prelogar is the Biden administration’s top lawyer at the court, defending the policies that are the source of much of Alito’s consternation. She responds to him with a steady pitch and precision. And she is not derailed by what he puts down.

Their jousting over issues such as abortion, vaccines, and all manner of regulatory power offers some of the most riveting exchanges heard these days at America’s high court.

When excerpts from their Supreme Court audio appear on YouTube or other social media, it attracts thousands of views, sometimes hundreds of thousands, as court-watchers debate who got the better of the argument.

Their back-and-forth provides more than drama in the white marble setting. Prelogar, 43, argues the government’s most consequential cases. And the exchanges with Alito, 73, have the potential to influence other justices and affect whether the government wins or loses.

Prelogar will be at the lectern on Tuesday in a major Second Amendment case, defending a law that prohibits persons subject to domestic violence protective orders from possessing a firearm.

Alito, a Trenton, New Jersey, native, once stood at the lectern that Prelogar commands today.

After graduating from Princeton and Yale Law School, he joined the Department of Justice and spent about five years in the early 1980s in the solicitor general’s office. President Ronald Reagan named Alito a US attorney in New Jersey and President George H.W. Bush tapped him for a prestigious appellate court post in 1990. President George W. Bush elevated Alito to the high court in January 2006, to succeed the retiring Justice Sandra Day O’Connor.

Prelogar, who grew up in Boise, Idaho, graduated from Emory University and then Harvard Law School. As a teen she entered state pageants and won the Miss Idaho title in 2004. She said she used the pageant scholarship money for law school.

“If you want to look at a through-line here, I like to go in front of judges,” Prelogar said recently about the experience on NPR’s “Wait, Wait … Don’t Tell Me!” The early pageant work may also contribute to her ease at the courtroom lectern and economy of language, shed of the usual “ums” and “ahs” that plague many lawyers.

Prelogar first became familiar with the inner workings of the Supreme Court as a law clerk to liberal Justices Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Elena Kagan. From 2014 to 2019, Prelogar was an assistant to the solicitor general arguing less prominent cases before the justices, and was separately detailed to an investigation into Russian interference in the 2016 presidential election, under special counsel Robert Mueller. In 2021, President Joe Biden nominated her to be US solicitor general, and the Senate confirmed Prelogar by a vote of 53-36. Only six Republicans joined Democrats to approve her.

Supreme Court oral arguments always begin with some element of suspense: How effectively will lawyers at the lectern make their case and what will justices reveal of their own views? The justices sometimes use these public sessions to press their own positions, with statements cloaked as questions, essentially beginning their negotiations with colleagues.

Any lawyer arguing a progressive position, as Prelogar regularly does, faces an uphill climb, because of the court’s conservative supermajority. For about a half century, the court was generally 5-4, conservative-liberal. Since 2020, it has been 6-3 conservative-liberal.

A few weeks ago, Alito and Prelogar sparred over a federal agency established to protect consumers from risky mortgages, auto loans and credit card deals.

The case began when payday lenders challenged the constitutionality of Consumer Financial Protection Bureau’s funding structure. Congress – seeking to ensure the agency’s independence – required it to be financed annually through the Federal Reserve System (which itself is funded through bank fees), rather than regular congressional appropriations.

It was a spirited argument, although the intensity in the courtroom as Alito challenged Prelogar’s justifications may be lost a bit in the cool words from a transcript.

“There have been agencies funded this way for every year of this nation’s history,” Prelogar told the justices, as she defended the bureau established after the country’s 2008 financial crisis.

Hear what happened inside the Supreme Court after historic ruling

“What is your best historic, your single best example, of an agency that has all of the features that the CFPB has …” Alito asked in one of his series of queries.

“I think our best example historically is the Customs Service,” Prelogar responded. “The first Congress created the Customs Service in 1789. It gave the Customs Service a standing, uncapped source of funding from the revenues that the Customs Service collected.”

Not satisfied, Alito continued: “What’s your best example of an agency that draws its money from another agency that, in turn, does not get its money from a congressional appropriation in the normal sense of that term but gets it from the private sector?”

“I can’t give you another example of a source that’s precisely like that one,” Prelogar said, “but I would dispute the premise that that could possibly be constitutionally relevant. This is a case about Congress’s own prerogatives over the purse, its authority.”

“So,” Alito declared, “I take it your answer is that you do not … But you think that to the extent it is unprecedented, it is unprecedented in a way that is not relevant for present purposes? Is that your answer?”

“Yes, primarily,” Prelogar said, adding with a bit of cheek. “I think it would be unprecedented in a way that you could say this is the only agency that has the acronym CFPB. That’s obviously true also, but it doesn’t track the constitutional value.”

Chief Justice John Roberts, who before becoming a justice also served in the solicitor general’s office and then as a private appellate attorney, was a superb advocate himself. Known for rigorous preparation, he was clear and conversational.

Roberts also acknowledged over the years how nerve-wracking it was. His hands would often shake before he stood up to argue, subdued once he grasped the sides of the lectern and began his presentation.

From the bench, Roberts is a tough questioner of Prelogar and Biden administration policy, but without the palpable antagonism that often comes from Alito.

During a January 2022 argument over a Biden Covid-19 vaccine requirement for federal workers, Alito began a set of questions with a tone that was alternately aggrieved and assured. He held the upper hand, as a majority of his colleagues were similarly skeptical about the reach of government power.

“I don’t want to be misunderstood in making this point because I’m not saying the vaccines are unsafe. The FDA has approved them. It’s found that they’re safe. It’s said that the benefits greatly outweigh the risks. I’m not contesting that in any way. I don’t want to be misunderstood. I’m sure I will be misunderstood. I just want to emphasize I’m not making that point,” Alito said.

“But,” Alito continued, as he confidently addressed Prelogar, “is it not the case that these vaccines and every other vaccine of which I’m aware and many other medications have benefits and they also have risks and that some people who are vaccinated and some people who take medication that is highly beneficial will suffer adverse consequences? Is that not true of these vaccines?”

“That can be true,” Prelogar said, “but, of course, there is far, far greater risk from being unvaccinated, by orders of magnitude.”

“But … there is some risk,” Alito interjected. “Do you dispute that?”

“There can be a very minimal risk with respect to some individuals, but, again, I would emphasize that there would be no basis to think that these FDA-approved and authorized vaccines are not safe and effective. They are the single-most effective.”

Alito cut her off: “No, I’m not making that point. I tried to make it as clear as I could. I’m not making that point. I’m not making that point. I’m not making that point. There is a risk, right? Has OSHA ever imposed any other safety regulation that imposes some extra risk, some different risk, on the employee?

Prelogar: “I can’t think of anything else that’s precisely like this, but I think that to suggest that OSHA is precluded from using the most common, routine, safe, effective, proven strategy to fight an infectious disease at work would be a departure from how this statute should be understood.”

As the two continued, talking over each other, they challenged the transcription service based on how many broken sentences and dashes were recorded.

When a clip of that exchange over the vaccine requirement of the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) was posted online, more than 500,000 people viewed it, and more than 6,000 people left comments.

The administration lost by a 6-3 vote along ideological lines.

Affirmative action and ‘the nation that we aspire to be’

Jeffrey Wall, who was a top official in the solicitor general’s office during the Trump administration, said the Biden solicitor general necessarily faces “headwinds with … a court that is more generally skeptical of government power.”

Speaking at a Practising Law Institute review in August, Wall overall praised the solicitor general’s record. “I think that General Prelogar should feel pretty good, all things considered, about how the term went,” he said.

Wall referred to the high-profile administration loss in the Harvard and University of North Carolina affirmative action cases last session, saying that “no one believes that those cases could have turned on the SG’s advocacy.”

The affirmative action arguments offered several Alito-Prelogar moments of tension. The Biden administration was backing admissions practices that considered students’ race as a factor in admissions to achieve campus diversity.

Prelogar highlighted repercussions for the military if racial affirmative action was eliminated at the service academies or colleges with ROTC programs that prepare officer candidates.

“What about a college that does not have a ROTC program,” Alito interjected, homing in on what he plainly saw as a specious ROTC reference and larger appeal to the military interest. “Would a plan that would be permissible at a college that has a program be impermissible at the latter, at the one that doesn’t have the ROTC program?”

“We’re not asking the court to draw that distinction,” Prelogar told Alito, asserting that the government’s interest extends “more broadly to other federal agencies, to the federal government’s employment practices itself, and to having a set of leaders in our country who are trained to succeed in diverse environments.”

“Well,” Alito countered, “then I don’t understand the relevance of what you’re saying about the link between college education either at a service academy or a school with an ROTC program and the needs of the military if it doesn’t matter whether the school has no ROTC program and therefore trains no officers.”

Prelogar said the military’s interest in diversity was not confined to the service academies. “We believe deeply in the value of diversity and in universities being able to obtain the educational benefits that correlate with diversity,” she said.

Alito later seized on Prelogar’s attempt to persuade the court to look at “the nation that we aspire to be”; he suggested the approach rang hollow.

“For corporate America,” Prelogar had said as she concluded her arguments in the dispute, “diversity is essential to business solutions. For the medical community and scientific researchers, diversity is an essential element of innovation and delivering better health outcomes.”

Alito told Prelogar it appeared she wanted to take the controversy at hand involving education and extend it to employment. “Is that right?” he asked.

“No, Justice Alito,” Prelogar said. “I was trying to make the observation that the experience of students in those four years of college have effects on the course of their life.”

“Then why were you talking about corporate America,” he rejoined.

“Because corporate America,” she said, “like the United States military, relies on having a diverse pipeline of individuals who had the experience of learning in a diverse educational environment and who themselves reflect the diversity of the American population.”

In the end, Harvard and the University of North Carolina, along with the Biden administration, lost the dispute by a 6-3 vote along the familiar ideological lines. Roberts, who wrote for the majority opinion that was signed by Alito and the other justices on the right wing, added a footnote that said the decision did not apply to West Point and the other military academies. (Students for Fair Admissions, the group that started the Harvard and University of North Carolina lawsuits, recently filed cases against the service academies.)

To be sure, not all Alito-Prelogar matchups end with ideological divisions. And indeed one of their earliest encounters found the two aligned, in a true theatrical situation, as the Washington-based Shakespeare Theatre Company staged a mock trial in December 2016.

The Romeo and Juliet tragedy was at the center of the mock case as it tested a wrongful death lawsuit brought by their parents (the Montagues and Capulets) against Friar Laurence, who had secretly married the young couple then helped Juliet fake her death.

Alito presided as the “chief justice” with four “associate justices,” two of whom happened to be then-lower court judges Brett Kavanaugh and Ketanji Brown Jackson (eventually elevated to the real Supreme Court).

Prelogar defended the Friar. Befitting the general theater audience and timing after the November 2016 election, her defense included various political and pop culture (Taylor Swift) references.

Of Friar Lawrence, Prelogar said at one point, “He just wanted to make Verona great again.” Then she delivered her closing remarks in a sonnet form, “because Iambic pentameter is exceedingly persuasive.”

After the mock panel deliberated, Alito and the others returned to the bench to deliver their ruling. He praised the lawyers on both sides of the case. “From now on,” he quipped, “I’m going to expect all the briefs from the solicitor general’s office to be in iambic pentameter.”

He then announced that Prelogar had prevailed in her defense of the Friar. Referring to the fact that the audience had separately taken its own vote, Alito joked, “Since this is a principality, it really doesn’t matter how the people voted.”

Prelogar, it turned out, won that vote, too.