Consider the geopolitical chaos:

- The Middle East in bloody upheaval – thousands dead, hundreds held hostage, no end in sight

- Outright anti-semitism surging on college campuses and in the city streets

- Oil at $150/barrel next year? (according to Bloomberg)

- A new Russian offensive in the Ukraine – “Putin is having a very good October” (according to The Washington Post)

- A paralytic Congress, lurching through fiscal showdowns and budget shutdowns

Consider the financial chaos –

- Treasury markets “in turmoil” (according to the Financial Times), or is it a “meltdown”? (Charles Schwab).

- Bond market volatility surging higher than stock market volatility by “the most on record” – (Bloomberg).

- The housing market is “painful, ugly, anxious” (CNBC), “completely broken” (Bloomberg) – “a crash that can sink the American economy” (CNN)

- The banking industry – to include even some of the great pillars of the financial system – has been shaky all year, balance sheets awash in unrealized losses that will take years to work out (see below)

And Yet – on Wall Street, Euphoria Reigns…

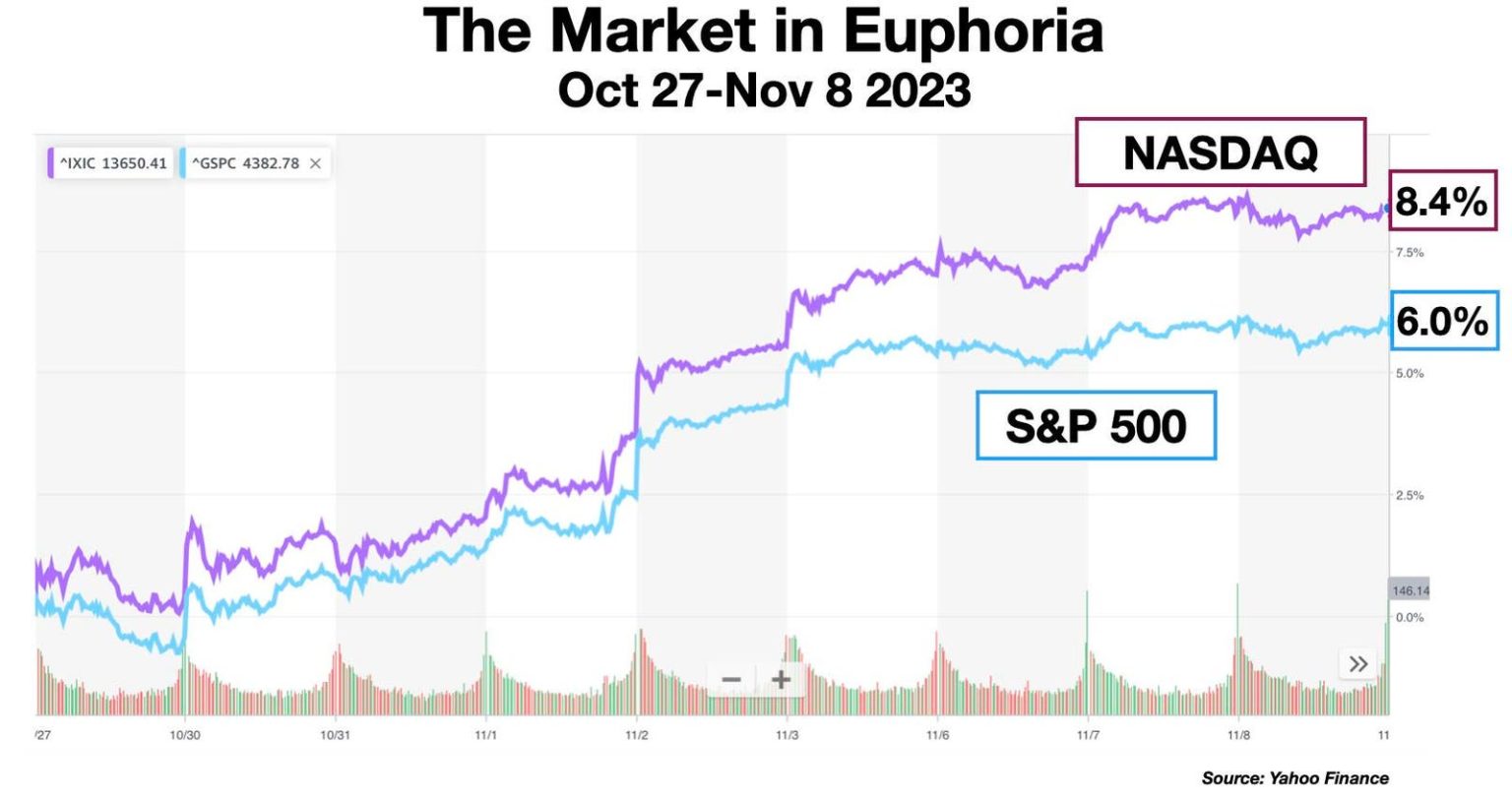

Last week, Nasdaq had its best week in a year. Since October 27, the index is up 8.4% .

It’s not just tech. The broad market is up. The S&P 500 has its best week since June 2022 – gaining 6% in the last 10 days.

What gives?

Well, haven’t you heard? It’s the Ceasefire…

Not the military ceasefire – that hasn’t happened yet, and probably won’t happen any time soon.

It’s something even more important (evidently) – it’s the Monetary Ceasefire.

The Federal Reserve has finally halted its carpet bombing campaign against the economy and the financial markets.

Let the news ring out: “The Fed is done.” (echoing from a chorus of experts – e.g., Rick Rieder, BlackRock’s CIO)

- “The Federal Reserve’s tightening cycle is over. After 11 rate increases since March 2022, totaling five percentage points, the Fed ought to be finished raising rates.” – Barron’s (Nov 6, 2023)

The Fed’s Terror Campaign

To review: the Federal Reserve launched its rate tightening offensive, more or less without warning, in March 2022. Perhaps they didn’t even realize what they were getting into. The Fed had been serving up dovish guidance to the financial markets for months. In June 2021, a majority of the members of the Federal Reserve’s Open Market Committee (FOMC) claimed not to see the need for any rate hikes at all in 2022.

By September 2021, there was a slight shift and a split vote. Of the 18 FOMC members, 9 predicted one increase in 2022. The other 9 still saw no rate rises ahead for 2022. For 2023, 13 members projected 2 rate hikes. 4 members saw just a single rate hike. (One optimistic unidentified member saw no need for any rate raises in 2022 or 2023.)

By December 2021, nerves were fraying a little. Two thirds of the FOMC now expected 3 rate hikes in 2022.

In the event, there were 7 rate increases in 2022, and 4 more in the first half of 2023. In the 493 days between the first increase in March 2022 and the last one in July 2023, the Fed jacked up the Fed Funds rate by 525 basis points.

It was the steepest tightening program since 1980.

The aggressiveness took everyone by surprise, including the Fed itself. Here is the Fed’s famous “dot plot” from September 2021. (This chart expresses the views of the FOMC members regarding the future levels of the Future Fed Funds Rate. Each dot represents the forecast of one of the FOMC members.) The average forecast Fed Funds Rate for 2023 (year end) was a little more than 1%. Reality weighed in at over 5%.

Obviously, the crystal ball wasn’t working. .

The Impact on the Banking Industry

Another group taken by surprise was the banking industry.

Bankers are generally not traders. They aren’t screen-watchers, set on a hair-trigger, ready to react quickly to breaking news and rapid market shifts. Bankers are slow and steady by nature. Out of habit, they expect continuity, not disruption.

The speed and intensity of the Fed’s rate tightening program was unprecedented. Banks were not prepared to pivot as quickly as the Fed had done. In particular, they weren’t ready for the sudden deterioration of their bond holdings. As the Fed’s action drove up the entire interest rate environment, and amplified the “interest rate risk” inherent in long-term bonds, the drastic drop in bond prices tore huge holes in their balance sheets before they could react.

The damage was massive. Long-dated Treasury Bonds –– the United States of America’s Full-Faith-and-Credit obligations! – lost more than one-third of their value in the 18 months since the Fed began tightening. Medium term Treasurys were down 14%.

Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) was the first and most spectacular victim. SVB’s unrealized losses — that is, the paper losses the bank was forced to recognize as a result of mark-to-market accounting on their holdings of long-dated Treasurys – quickly mounted.

- “The Federal Reserve’s increase in rates over the last year greatly reduced the market value of SVB’s investment portfolio — about $15.9 billion in unrealized losses in the third quarter compared to the company’s $11.9 billion of tangible common equity.”

[Note: The paper losses were actually a bit higher — see below.]

The post-mortems on the SVB collapse have identified many contributing factors, from a too-high level of uninsured deposits and insufficient hedging, to the lack of a Chief Risk Officer for much of the critical period. But these factors are ancillary. The main cause of the bank’s collapse was its failure to anticipate the unprecedented ferocity of the Fed’s campaign. Which, as shown above, even the Fed itself did not anticipate.

It was common in the post-SVB narratives to describe it as a failure to follow the rules of “Banking 101.” And indeed, interest rate risk is a standard topic for Banking 101. But what was not a 101-level topic was a scenario where an activist Central Bank, to show its moxie, decided to accelerate the big interest rate flywheel faster than it was really designed to go. The slow-and-steady men and women – both at the banks and at the Fed itself – did not recognize quickly enough the complex way in which rising rate risk would interact with changing and sometimes obtuse accounting rules. They did not understand how the process would speed up in a technologically amped up eco-system and suddenly rip big holes in the banks’ balance sheets. They did not see that the banker’s traditional conservative mindset – normally seen as an asset – could become a liability in this new context.

The Fed’s Blind Spot

Did the Fed recognize the risks it was creating? Does it even today acknowledge a policy error? I’ve read through the Fed’s after-action report on SVB, published in September. It is not clear that the Fed yet understands the problem they created. All of the report’s recommendations focus on strengthening bank supervision. The official report addresses the matter of interest rate risk as though it were some sort of natural disaster that SVB did not take sufficient precaution against.

- “During a period of low interest rates, SVB invested a large amount of the influx of deposits in securities with long-term maturities, specifically U.S. Treasury bonds and agency-issued mortgage-backed securities.”

This would likely have been viewed at the time as a safe and prudent way to earn interest on SVB’s cash balances without taking on credit risk.

But then “when interest rates started to rise in 2022, SVB did not heed the early signs of market risk.” – [Emphasis added]

This makes

- and the rising rates adversely affected the value of SVB’s investments in securities with long-term maturities…Interest rates continued to rise and the bank experienced a significant increase in unrealized losses on its investment securities, from approximately $1.3 billion and $313 million for its HTM and AFS portfolios, respectively, at year-end 2021 to approximately $15.2 billion and $2.5 billion for its HTM and AFS portfolios, respectively, at year-end 2022.”

In other words, as the Fed sees it, the fault lies with SVB and its failure to adjust “when interest rates started to rise.” But interest rates did not just “start to rise.” The phrase reveals the blind spot at the central bank. Interest rates were rising because the Fed was forcing them to rise. Perhaps there was good reason for this tightening policy (or perhaps not — see below), but what one looks for in this report, and elsewhere, largely in vain, is a recognition that the Fed itself failed to foresee the impact on the banking system of going into Fast and Furious mode.

The Contagion

Silicon Valley Bank was not the only casualty. The contagion penetrated the entire financial sector.

Several other regional banks went down. Even the biggest banks were hit hard. Bank of America seems to have suffered the worst. On October 17, Reuters reported that

- “Bank of America reported unrealized losses of $131.6 billion on securities in the third quarter, growing from the second quarter [when it reported $106 Billion in unrealized losses in its securities holdings]… ‘All of these are unrealized losses on government-guaranteed securities,’ Bank of America’s chief financial officer told reporters on conference call discussing third-quarter earnings.”

“Government-guaranteed securities” – yes they were. SVB and these other banks were parking their cash in what they thought were the safest of asset classes, US Treasurys. Their mistake was not in buying Treasurys, nor in failing to understand interest rate risk per se, but in not anticipating the speed and intensity of the Fed’s onslaught.

Today the banking industry as a whole is estimated to be carrying over $600 Billion in unrelated losses on their books – which “could squeeze their finances for years to come.” Banking shares are down 40% against the S&P 500 since the SVB crash. In short, the financial sector is depressed – and it will stay depressed until it can work out of the deficit created by the Fed’s terror campaign (and absurd mark-to-market accounting complexities). Or until rates fall, and prices rise, allowing for a revised mark-up to market. But with all the talk now about “higher for longer” — well, it may be a long wait.

“The Fed is Done”

In any case, this kneecapping of the banking sector by the unelected economists at the Federal Reserve is a demonstration of the Fed’s awful powers over the market and the economy. The effects of the Fed’s terror campaign have gone beyond just snuffing a few high-flying regional banks. It has also paralyzed the housing market, and may have seeded a recession.

And for what?

The rationale for the tightening campaign was to control inflation, but (as has been described in several previous columns and now in many other sources) the Fed’s policy has had little if any impact on this inflation. It has not reined in consumer spending. It has not dampened the labor market. It has created huge problems for foreign countries and businesses that financed themselves with dollar-denominated debt.

- “Many smaller emerging markets are confronting a “silent debt crisis” as they struggle with the impact of high US interest rates on their already-fragile finances, the World Bank has warned.” – The Financial Times (Nov 7, 2023)

It has stimulated capital flight from China (and many other countries). According to the World Bank —

- “Since March 2022 [when the Fed started its campaign], there has been a large capital flight from emerging markets and developing countries, leading to declines in their foreign exchange (FOREX) reserves, local currency depreciation and difficulties to repay dollar denominated loans.”

A side-effect of Fed policy aimed (ineffectually) at mollifying American consumers annoyed at the temporarily high price of eggs and gasoline has been a huge disruption of government budgets all through the developing world. The terror campaign has done nothing to resolve shortages in semiconductors or eggs or used cars or lumber or any of the transitory price increases which have now slowed and in many cases gone into reverse — all on their own, through the natural working of he market mechanism.

In any event, this is why the financial markets are now elated. The monetary terror may be over. The markets welcome the monetary ceasefire – which everyone hopes will become now a permanent peace. That is what Nasdaq’s surge over the last week was all about. The market has learned to fear the Fed more than anything else – more than recession, more than war in the Middle East or $150 oil, more than Putin’s missiles. When that fear is (perhaps temporarily but blessedly) lifted, the response is a grand relief rally that is oblivious to all the other perils of this perilous moment in world history.

But Is The Market Broken?

Euphoria – or Ceasefire – is pleasant enough (while it lasts). But the larger question about the Fed’s monetary ceasefire, and the market’s reaction to it, and the apparent obliviousness of investors to the “real world” crises exploding all around them, is whether this strange relief rally is a sign that financial markets have become dysfunctional, whether they no longer perform the service of allocating capital efficiently based on economic fundamentals. Instead, they seem to have become a rather narrow focused barometer of policy trends and ruminations at the Federal Reserve.

This is a visible, measurable phenomenon. Since the mid-1990s, the Fed has become the single most important market mover. This is clear from a study by two Fed (!) economists.

- “Since 1994 about 80% of realized excess stock returns in the U.S. have been earned in the 24 hours before scheduled monetary policy announcements. …. The S&P500 index has on average increased 49 basis points in the 24 hours before scheduled FOMC [Federal Open Market Committee] announcements. These returns do not revert in subsequent trading days and are orders of magnitude larger than those outside the 24-hour pre-FOMC window. The statistical significance of the pre-FOMC return is very high.”

The market seems to have become a dependent variable hanging on the pronouncements of the Federal Reserve, the tone of the minutes of the FOMC meetings, and the speeches, gestures, slips of the tongue and eyebrow twitches of its leadership. Why worry about subsidiary factors like corporate earnings, or the implications of the Hamas outrage, when the main game is now all about what the Fed will say or do next?

For , see also:

Read the full article here